FILMOGRAPHY

Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex* *But Were Afraid to Ask (1972)

Love and Death (1975)

Annie Hall (1977)

Interiors (1978)

Manhattan (1979)

Stardust Memories (1980)

A Midsummer Night’s Sex Comedy (1982)

Broadway Danny Rose (1984)

The Purple Rose of Cairo (1985)

Hannah and Her Sisters (1986)

Radio Days (1987)

September (1987)

Another Woman (1988)

Alice (1990)

Shadows and Fog (1991)

Husbands and Wives (1992)

Manhattan Murder Mystery (1993)

Bullets Over Broadway (1994)

Mighty Aphrodite (1995)

Everyone Says I Love You (1996)

Deconstructing Harry (1997)

Celebrity (1998)

Sweet and Lowdown (1999)

Small Time Crooks (2000)

The Curse of the Jade Scorpion (2001)

Hollywood Ending (2002)

Anything Else (2003)

Melinda and Melinda (2004)

Match Point (2005)

Scoop (2006)

Cassandra’s Dream (2007)

Vicky Cristina Barcelona (2008)

Whatever Works (2009)

You Will Meet a Tall Dark Stranger (2010)

Midnight in Paris (2011)

To Rome With Love (2012)

Blue Jasmine (2013)

Magic in the Moonlight (2014)

Irrational Man (2015)

Cafe Society (2016)

Wonder Wheel (2017)

A Rainy Day In New York (2019)

Rifkin’s Festival (2020)

Coup de Chance (2022)

FILMOGRAPHICAL SUMMARY

The comedic genius Allen Konigsberg was born in the Bronx, in 1935, to Nettie and Martin Konigsberg, working class Jews of Austrian and Lithuanian descent. He was raised in Brooklyn, in the Midwood neighborhood, which would later be loosely rendered (and marvelously romanticized) in one of his masterpieces, Radio Days. At the age of only 17– still on the high school baseball team, sports one of Allen’s professed pleasures– his gags began to be featured in newspapers and his astonishingly effortless comedic gifts began to be noticed. Anticipating a career, he legally changed his name to more tolerably goy “Heywood Allen,” transmuted finally to “Woody Allen,” emerging as a perfectly digestible handle for a comedian in this occasionally anti-semitic America who did nothing at all to suppress his Jewishness.

He became, naturally, a comedic writer for television. He worked alongside a laundry list of the luminaries of the time. But first, young Woody (still only 19) flunked out of NYU’s film studies program, later a joke in his brilliant Annie Hall: “I was thrown out of N.Y.U. my freshman year for cheating on my metaphysics final. I looked within the soul of the boy sitting next to me.” Very soon, and throughout the 1960s, this shy, claustrophobic, introvert became one of the most unlikely and influential stand-up comics in the history of the form. As this is not a study of Allen’s life, I won’t dwell on this era except to say that he was every bit as good, if not better, in this first career. He changed the form, turned slender Greenwich Village stages into something approximating a psychoanalyst’s couch. So many of his bits are still uproariously funny and illuminating, still do, in fact, reverberate today without a trace of age.

The persona he developed as part of his routine was an exaggerated melange of self-effacement, insecurity, nebbishness, neuroticism, intellectualism, and so often used as its foundation the tenets of “schlemiel comedy” that has laced its way through Jewish humor for centuries.

Some time later, he took a class at Columbus Circle in a dumpy classroom with the Hungarian ex-pat-cum-drama-teacher, Lajos Egri. “There was no one in the class under forty-five years of age and nobody knew what they were doing…,” Allen later recalled. Allen’s gifts– as true creative gifts are– were in many ways inexplicable, natural, seemingly instantaneously developed. Yet it requires but one read through Egri’s “The Art of Dramatic Writing” to recognize the method, the clarity, concision, and sense of purpose that eventuated in the 50+ films he would proceed to write and direct over the next six decades. Aside from almost certainly being among the most practical books on dramatic writing ever written, listening to Allen talk about his films betrays its impact. In the documentaries and interviews on his career– including perhaps the best, that directed by Robert B. Weide, a staunch defender of Allen through his later “scandals”– Woody and his interlocutors practically speak of each film as if they are trying to distill the Egrian essence of each premise. The first two in the six theses Egri submits as the foundations of drama are:

- All human beings are fundamentally selfish, their primary drive being to feel, or be perceived as, important.

- Human character is fixed and does not change significantly over life.

At the intersection where these two premises collide with Allen’s demonstrable infatuation with Freudian psychoanalytics, Dostoyevsky, Kafka, existentialist philosophy, death, particular strands in the cinema (his near-deification of Ingmar Bergman and Fellini, for example), and romantic nostalgia might materialize some very uncertain Rubik’s Cube that could perhaps align and reveal his art.

But that, of course, would be too simple. Because all of those qualities Allen developed in the comedy houses also permeated his work. So what emerged was uniquely funny, and uniquely resonant, and came to typify his approach so deeply that both his persona and his work quickly grew inseparable.

He began to write prose, much of which was published in the New Yorker, beginning in 1969, and later in a few slender volumes: “Getting Even”, “Without Feathers,” and “Side Effects”. His voice was so singular that it was both instantly recognizable, inimitable (though many tried), and inevitable. That urge to ask: “why had no one thought to do it this way before?” That feeling which tends to pull the reader or viewer under the artist’s spell: Allen would later frame this ability, and its attendant questions, in dozens of ways in his films.

There were easily discernible qualities in Allen’s work that led to his explosive popularity. For an introvert, he was extremely candid and vulnerable. An example of a character trait that would later bite him in the ass, he was not at all squeamish about sex. In fact, he viewed sex as perhaps the principle gateway to the psyche and most fertile psychological grounds to traverse in his work (“I don’t know the question. But sex is definitely the answer.” ““Love is the answer, but while you are waiting for the answer, sex raises some pretty good questions.”) As a true bard would, he viewed sex and romantic love, naturally, as a universal domain of shared experience. In his standup, he used anecdotes and jokes about his own love life as a means of bringing his audience closer to his material. In his films he pushed these ideas into strikingly honest and potentially perilous places. Audiences thought they were getting closer, perhaps, to the true flesh and blood Woody. They may have been, but there is also this tendency to want to read autobiography into his material, because he was such an effective author of character.

This blending of fiction and fact is potentially also a consequence of the rare degree of respect he showed for the intelligence of his audience, readers, and viewers. He did not condescend and he did not soften the implications of his worldview. Even toss-away lines delivered by bit-part characters– “If Jesus came back and saw what was being done in his name, he’d never stop throwing up.”- stung. In his jokes were laughs such that the truth hurt. His comedy belied his nebbishness. It was actually often brutally honest: “Life is full of loneliness, suffering, and unhappiness, and it’s all over much too quickly.” “The most beautiful words in the English language are not, ‘I love you.’ They’re, ‘It’s benign.‘” “I believe there is something out there watching us. Unfortunately, it’s the government.” In Allen’s comedy was a sense of the human experience as mutually painful. That it not only could be, but must be, laughed at. Where he absented that comedy purposely was where Allen sailed into more uncertain seas, and the vessel he rode (almost always Bergman- or Dostoyevsky-inspired) tended to leave the sense of nihilism in its wake, in the form of his many heartlessly spurned and callously murdered.

So, compelled by this highly relatable and universal comedy, his best work was received not merely at face value, but at that kind of value that is accorded to things in which the receiver comes to digest into their marrow. Things that they come to “possess” as “their own”– that, as the cliche goes, “rewire” their perceptions. Allen’s films came to be not just films. Even though we’ll discuss his tendencies toward reinvention, his each release was attended by “Woody Allen Movie” expectations that went some way toward never affording his true experiments the appreciation they deserved.

It’s difficult for anyone born after 1990 to believe, but there was a time when one went to a Woody Allen film in order to go back to a sense of shared human experience, of real empathy. He achieved degrees of clarity, verisimilitude, and the stab of emotional truth in his characters in so many moments that it is difficult to find a film void of at least some interest. He was astonishingly brisk in his dramatic style, even though the structure of his plots could often be deceivingly complex. He achieved this, like a good comedian would, by building an emotional and/or comedic accumulation in his material. At the risk of vagueness, his best films blossomed. In his best films, what came next made all that came before more resonant. Ironically, given some vociferous accusations of sexism and of life choices he made that we will discuss (which broadened those claims), he was a dynamic chartist of the mores, charms, and vagaries of both sexes. As a man, he wrote so many dynamic women that if his critics sat and took both a deep breath and an accounting, they might calm.

How to reckon with his cinema? Why, though he made many cosmically wonderful films, did they seldom rise to the level of his cinematic idols? He made so many good films, that it seems each critic and fan has their own list of what they consider masterpieces and these are comprised of a startling number of films. Yet he is seldom spoken of with any degree of veneration. In his later career, one reason for this was rather obvious. But another key to this mystery could be his age and his working habits. He did not direct Annie Hall until he was 41 years old. He then proceeded to make films so quickly and consistently that it almost beggared sense. Like Bergman, Allen’s body of work is so massive that it consternates. Had he started his career with films (he certainly had the talent) it would be truly unwieldy. But these many works came less haphazardly than the troubled, workaholic Bergman. His energies– both physical and creative– kept with an idiosyncratically ordered and routine pace. He struck very few true lows, but neither did he allow himself the kind of creative madness that accidentally congeals into those astonishing highs he so admired. As mentioned, he was endlessly reinventive, but only as he reframed work that was, for more sterling artists, once the brazen stabs of risktakers. Allen took few true risks. He was simply working too quickly. Later, as his perceptive abilities weakened, the “film-a-year” Allen seemed to be churning out pictures in almost obligatory fashion.

His directorial career began in earnest in 1969, naturally, as a comedian, by making his “early funny movies”. In 1977, he pivoted, and declared with one of his greatest films that he’d found his true calling. From this point, one lens through which to view his work is through the series of cinematographers with whom he collaborated to greater or lesser success.

Those early comedies necessarily ran through a series of adequate professionals who didn’t get in the way of the laughs.

Then from 1977’s Annie Hall until 1985’s The Purple Rose of Cairo, Gordon Willis’ contribution simply cannot be overstated. It is not unreasonable to argue that these were, in their totality, “Allen/Willis films.” Willis was an artist of austere perfectionism and he influenced Allen’s every decision, even the very blocking of scenes. He accelerated Allen’s cinematic growth-curve so much that it is not too much to say that the contours of Allen’s career would have been totally different without his contribution. There was in these films sense of where things “should be”, more than ever a sense of “mise en scene” and its constituent parts, that Allen would achieve with no other cinematographer. This frequently resulted in images of such compositional and luminous beauty that certain shots could double as museum pieces. “The Prince of Darkness” as he came be called, Willis was a lunatic with light. If he was to have a coin of it at a precise moment fall on the forehead of an actor, it would be because they hit their fucking mark. But he was austere even with that very light, most notably in Interiors. He made you strive to see, to lean in and look more closely. When Black & White was considered anathema, Willis completely reimagined its usage and impact. These images seemed set in a mythic past, a storybook history of New York. Manhattan, Interiors, Stardust Memories and Broadway Danny Rose have textures such that they stun.

Beginning with Hannah and Her Sisters in 1986 through to 1997’s Deconstructing Harry, Allen worked with Carlo Di Palma on 12 films. Most noted for his work with Antonioni, his approach was less technically austere, less sophisticated perhaps, and more exploratory. He was much less the tyrant. Ironically, much of the images he rendered still had a look of “sophistication” that was, in a sense, a veneer, a patina, much like the very characters of Hannah and Her Sisters. And not surprisingly, he shot New York like a European. This lent films like Alice a certain strangeness that enhanced the material. When he and Allen truly synchronized, the results were marvelous. The pinnacle of their collaboration, Radio Days, was astonishing for both its workmanlike, ground level intimacy and the nostalgic beauty of certain set pieces. But Di Palma was quite well suited for a filmmaker who– just one example of Allen’s profoundly idiosyncratic psychology– simply insisted on making film after film after film at the pace of exactly one per year. Allen later called him a “hunt and peck primitive”. There are ways of reading this comment, and the most likely is as very affectionate, because hunting and pecking was what Allen did, movie after movie.

Sven Nykvist shot a few films in this era. Bergman’s similarly austere framer of light lent images both grave and sumptuous to Crimes and Misdemeanors and, more notably, Another Woman, where he managed to achieve gravity without seeming stuffy.

From 2000 on, like Woody’s movies, his collaborations and their respective output grew erratic. Zhao Fei, Wedigo Von Shultzendorff, Remi Adafarasin, Javier Aguissarobe all worked to rather bland results. The three films he made with the legendary Vilmos Zsigmond were modestly more disappointing than successful.

By far the finest output of this era was aided by the brilliant Darius Khondji, who returned to Allen’s work that warm, gilded sheen a nostalgic fantasist so adores. The best of these, Anything Else and To Rome With Love, are sumptuous in the extreme, but not so much as…

Vitorio Storaro, who bathed and rebathed and overbathed Allen’s final run of films, such as A Rainy Day In New York and Wonder Wheel, with amber and tangerine hues that positively soaked the screen into occasional beauties, rendered certain shots ridiculous, and later pointed to rumors of colorblindness, a joke not lost perhaps on the man who directed Hollywood Ending.

Finally, the films themselves:

His “early funny ones” (Woody, who cited this era by proxy in Stardust Memories, was to some degree his own mythologist) were all quite funny and mainly just that. Take the Money and Run (1969), Bananas (1971), Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex (1972), Sleeper (1973), Love and Death (1975). Most surprising in these early pictures was the intelligence. Allen, ever cerebral, in this crosssection addresses political violence, sexual deviancy, techno-fascism (and techno-idiocy), and history as literary device.

Annie Hall (1977), his first masterpiece, was, of course, a watershed, both for him and for the cinema at large. Oft imitated, very seldom matched, and pretty much never in terms of individual vision, in this fiercely creative picture film form and character merge so completely that the movie is essentially told in a cinematic first-person, both past and present that has an incredibly engaging energy of which it is difficult to find an analogue. This is not simply because of Allen’s compelling voiceover, nor only because of his unusual direct-address elimination of the fourth wall, nor only because of highly finely tuned is the film’s perspective. Woody’s personality always stood at the forefront of his billings, but this is perhaps where art and artist, work and maker, real-life Woody and vaguely disguised on-screen Woody, became similarly inseparable in the eyes of viewers. Allen culled from life with little filter. He was also mature in art and life. His 8th film, at 41 years old, much of the material is pulled directly from his prior, very fruitful career. So the film, from a screenplay by Allen and Marshall Brickman, is called Annie Hall, but it is in truth a kind of kaleidoscopic biopic of the comedian “Alvy Singer.” It is kaleidoscopic because it is structurally unique, effortlessly jumping through time. He allows characters to collapse the internal logic of their own timelines, to talk with one another or comment on each other like time travelers. He establishes character and so quickly is able to run them through dramatic vicissitudes that are ruthlessly logical in their probing of the illogic of romantic relationships. The film is also effortlessly funny, truly bittersweet in its romance, and unsentimentally poignant, managing to be wise without being pat. It is one of those great films that is perhaps lessened when written about. It must be watched because it is something that not nearly enough films are: uniquely cinematic.

As I wrote above, Allen constantly tried to new things cinematically, but his material was still often derivative of finer work. Interiors (1978) is one such example. Allen exhibits truly magnificent dramatic clarity and the cumulative impact of his rather brilliant characterization is undeniable. It is a clarity, however, that is almost suffocating. Characters state their mores and traumas with such sober articulation one wonders what universe they inhabit. The material feels written at a strange remove. The dialogue is in a strange diction. Whose work is this really? Critics stumbled over themselves to attribute influences: Chekhov, O’Neil, one even suggested Joseph Mankiewicz. But the Rosetta Stone, of course, is Bergman. Even still, as Gordon Willis and Allen frame stoic faces in Persona-like repose as they look out of frigid beachfront windows, the images are unforgettable.

Manhattan (1979) dares many things. It dares to be about the loves and mores of the selfish and insular and it achieves this with a rare degree of psychologically acuity. It dares to be about self-contradiction, how we perhaps implicate ourselves with our own hearts, and with mind both male and female which beguile in their depth given the economy of the film. It dares to be about a much older, divorced father, dating a much younger woman– a teenager, in fact– because he’s neither grown up nor does he seem to have a sense of moral responsibility not gleaned from his neurotically insular interpretations of books and culture. That teenager, played brilliantly by Mariel Hemingway, is the heart of the film. She is both girlish and far more wise in her insecure insinuations than she has any right to be, and for those who decry the film for a leering creepiness or for the abdication or normalizing of inappropriate relationships, the film foists the joke back on them. It is very self-aware. It is also daring in its romantic nostalgia and here also self-aware. Here the perfectionist austerity of Interiors is transformed by Gordon Willis into pictorial grandeur and museum-piece silhouettes of such consistent compositional and luminous beauty that his photography will survive on certain shortlists perhaps for centuries. He does this in black & white and the film opens to Gershwin’s Rhapsody In Blue and, like Gershwin, it is appropriately cheesy while remaining stunning. The film is not perfect, but it is a masterpiece of a kind.

Stardust Memories (1980) weaved more ideas from Fellini and Bergman into a threadbare meta-film tapestry. It had moments powerful and yet delicate, such as an extraordinarily performed and directed revue of psychosis by Charlotte Rampling. The central romantic whimsy afforded in the repartee of Allen and the beautiful Jessica Harper is an Allen trope perhaps wrought most finely here. Willis’ cinematography is again astounding. But it is hard to divine the point of the film, which is not so much about what works an artist should make in the face of the fact of death, but about whining about how popular success muddles the question. One wonders perhaps why Allen isn’t just making another of the films he’s inclined to make, as opposed to simply commenting on doing so. In fact, he is, and that’s part of the wry cleverness of the picture, which ends on a shot that is visually and textually mythopoetic.

If one were to attempt a taxonomy of Allen’s films, Broadway Danny Rose (1984) would be a particular species. Call it the “nostalgic fantasist comedy,” again shot in stunningly textural black and white by Gordon Willis. It has some of Woody Allen’s most effervescently delightful writing and a real heart, along with an ending that saddens and delights.

Allen then made another near masterpiece of the kind of tenderness and empathy that made Danny Rose such a wonder. The Purple Rose of Cairo (1984) is whimsical, saddened, and, though somewhat slight, culminates in an emotionally truthful stab. The ending was such a risk that Allen practically never dared its kind of energy again. Rarely did he manage to so imbue his characters with warmth and then so ruthlessly spurn them. It is a drama more effective than any of his later obvious capital-D Dramas tried to be. It starts with loveliness: “My God, you must really love this picture,” Jeff Daniels’ Gil Baxter at one point says to Mia Farrow’s mousy, delightful daydreamer, Cecelia, as she fritters away her miserable days in the glowing comfort of the movie house. It is the kind of movie that has you considering in how many ways such a statement can resonate. And then it ends in a despairing resignation that is so honest that it almost annihilates its own illusions, and in failing that only further confirms them. The film is a wonder.

Hannah and Her Sisters (1985) had Allen switching cinematographers, to the Italian lensman Carlo Di Palma, a tremendous change. And, indeed, he would never again have such a vibrant run as he had with Gordon Willis. Di Palma lent Hannah and Her Sisters precisely what the film seemed to need: a patina of sophistication. In truth the film is very, very simple, basically a couple of bland stories framing an excellent short comedy. The performances are, however, astonishingly strong, particularly Diane Weist, as Holly, one of Allen’s most nuanced women. The film also has a million small charms, and an ending that was contra-Purple Rose in its optimism. Thus, it was quite successful commercially.

Then followed Allen’s second masterpiece, Radio Days (1986). This will seem to many an Allen enthusiast an odd film to champion. Please look again. It is the picture that encapsulates Woody’s unique contribution to American culture most vibrantly. Allen, to this point, had contributed massively to the American Cinema. His greatest contribution to American culture, however, both predated his films and then later imbued them with the characteristic brilliance that was his auteur stamp: his effortless genius for cerebral comedy. Radio Days was the greatest exhibition of the Allen comic sensibility. It is in almost every respect revue of his finest instincts across all mediums, even his prose work. In an unfortunate (read: cowardly) vivisection of Allen’s work by the then-head critic of the NY Times, A.O. Scott, in January of 2018, is this passage regarding this work: “Mr. Allen’s prose made an even stronger impression on me than his films. His characteristic deflationary swerve from the lofty to the absurd, from high seriousness to utter banality, struck me as the very definition of funny.” While his article is shameful, this statement is a wonderful way of encapsulating the energy of Radio Days. And aside from this pendulous comedic brilliance is a rendering that is so artful as to astonish. Everything, from the extraordinary art direction and set design of Santo Loquasto, Carol Joffe, Leslie Bloom, and George DeTitta Jr., to the period music and costume, to Carlo Di Palma’s vibrant frames, to the perfectly pitched performances of the voluminous cast, was historical filmmaking of the highest order. It was and is still hard not to be fulsome.

September (1987) was a modestly successful chamber drama– for Allen almost experimental given its scale– that he shot and then completely reshot with a different cast.

Another Woman (1988) was Allen’s most successful drama and remained so, in my estimation, until the end of his career. Though he seemed almost incapable of making a drama without appropriating something of Bergman or Dostoyevsky, here the picture is through Gena Rowland’s performance an exhibit of a very rare kind of empathy. The ever-cerebral Allen sought, much like Bergman with Wild Strawberries, to understand why and how a particularly unlikable woman should come to love both herself and others with passion and he did so beautifully, made more beautiful yet through the lens of Bergman’s longtime collaborator, Sven Nykvist.

Alice (1990) was experimental (and successful) in a different way: a blending of the “sophisticated” artistic patina of Hannah with a whimsical comedy hearkening back almost to Allen’s “early funnys,” or at least to Stardust Memories. Given the coming personal trauma, it is difficult to watch the film and not feel that Allen had at one time a great deal of sincere love for Mia Farrow.

Shadows and Fog (1991) was probably Allen’s first true failure. John Cusack gives his scenes an interesting and very casually compelling energy, but the picture is such an odd mess of seemingly unfinished ideas and it is a rather lame allegory.

Husbands and Wives (1992) shifted Allen’s cinema. Though he had to this point in his career drawn much of his material from life, that material was largely benign. His relationship with Mia Farrow dwindling into lovelessness, and with perhaps some burgeoning sense that it would end in a certain very unsettling way, he directs this ruthless cinema-verite simulation of the disintegration of two marriages and exhibits most forcefully his nearly sociopathic, borderline autistic ability to cull material from the contemporaneous pain of others.

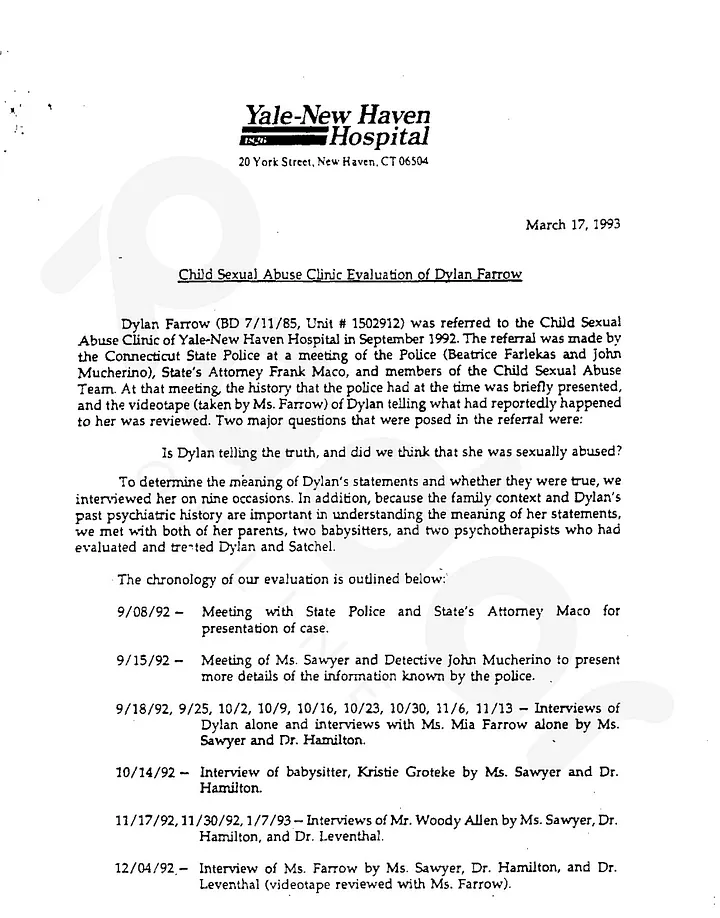

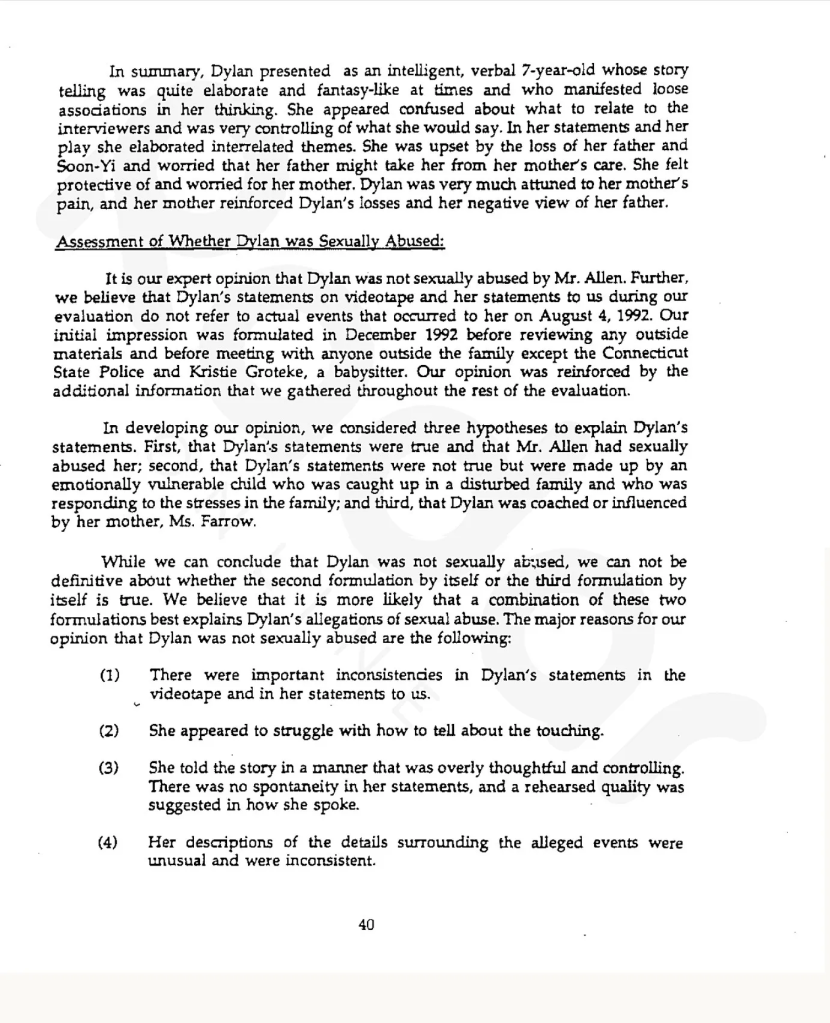

During the development of Husbands and Wives, Allen had an affair with Soon-Yi Previn, the adopted daughter of his long-time girlfriend and collaborator, Mia Farrow. The unusual and painful events culminated in a break-up, a nasty custody battle, and eventually in a particularly horrific accusation. Mia and Dylan Farrow claim that on August 4th of 1992, at the Farrow family estate in Bridgewater, CT, Woody Allen molested Dylan, then 7-years-old. The accusation was investigatged twice and was determined both times to be unfounded. Nothing since has come to light to change this judgment. This, to my mind, is unavoidably important to reckon with as regards this project. I write about these events here. They are critical to understanding Allen’s subsequent cinema and how his prior cinema refracted in the lens of these accusations. The entire ugly matter is also like a Rorschach blot for mindful moviegoers and raises many pertinent questions around the question of art and the artist.

Allen then made three consecutive comedies:

Manhattan Murder Mystery (1993) was so light as to barely show up on the screen, and the fact of its being– at one point– half of the screenplay Annie Hall (this is hard to imagine, but its true) is a study in qualitative contrasts.

Bullets Over Broadway (1994) featured a host of strong comedic performances, one (Jennifer Tilly) at the time one of the shrillest to ever grace the screen. There was illuminating, maybe troubling philosophical conjecture in the material. Was it sincere, this implication that art is a religion more sacred than human life, that the artist is not beholden to the tenets of any organizing morality in that he “makes his own moral universe”? Was Allen by couching it in this mess of misfits pointing out the unsustainability? Was Rob Reiner’s hideous Sheldon in fact a take on the hideous, bloviating, rotund Allen-hater, Orson?

For sheer shrill, Mira Sorvino outdid Jennifer Tilly the very next year in Mighty Aphrodite (1995) . Her performance ruins the movie for some, but not the Academy, who awarded her Best Actress. The movie is quite slight, and it has its issues, but it ends on a note of bittersweetness more successful than nearly any such stab in Allen’s oeuvre.

Woody then directed his first and only musical, Everyone Says I Love You (1996), a sensational entertainment starring a remarkable ensemble. The film is wonderful for many reasons, but mostly for its winking wryness, its blend of satire and class commentary and sincere nostalgia. It was Allen’s most successful comedy since Radio Days.

Then came the acerbic, intentionally tasteless Deconstructing Harry (1997), Allen’s most original film perhaps since Annie Hall. One could (and many did) simplify it into something akin to Philip Roth’s Zuckerman Novels made cinema, but it was more clever than that, and much more dismal fun than that would probably imply. The film is the story of a writer who uses salacious details from the people and events from his life as fodder for his short stories and novels. They are as ugly as he is, and Allen doesn’t leaven things. His screenplay cleverly intersperses his plot with cinematic dramatizations of them. Part of the brilliance of the prismatic structure of the film is that, after time, one tends to forget who is the real character and who is the fictional representation.

Even more embittered, Celebrity (1998) was a failure for a host of reasons, not the least due to a misdirected central performance by Kenneth Branagh. It does, however, feature an absolutely caustic performance by Leonardo DiCaprio, as a psychotic young movie star and a Charlize Theron turn that is vicious.

Sweet and Lowdown (1999) was a good idea, but it was poorly written and executed and a sense of real bitterness was beginning to suffuse Allen’s work. Samantha Morton was simply wonderful to be held in similar esteem to Sean Penn’s hokey performance. In some ways the film was as ugly as Celebrity. It’s not that it wasn’t funny, but its comedy was embittered.

Small Time Crooks (2000) leavened things a bit, a straight comedy with a clever structure and wonderfully funny performances by Tracy Ullman and Elaine May.

The Curse of the Jade Scorpion (2001) was lovely to look at, and forgettable to watch.

Holywood Ending (2002) had it moments. It had Allen, at 67, still stretching his age to snapping. Not only was he portraying a Hollywood director “down on his luck” (at this age!), but he was somehow also 34 year old Tea Leoni’s lost love, and returning to the slapstick comedy he so wonderfully pulled off when he was actually Leoni’s age. It wasn’t bad.

Woody’s first post-9-11 production, the ambitious Anything Else (2003), uttered not a word of the events of that fateful September day, but yet a post-traumatic energy imbued the film. Misadvertised on its release, the movie obstinately refuses to ever become what you’d expect of it. It is written of as a grim spiritual sequel to Annie Hall. This is only partially true. In a broader sense, it’s a spiritual nightmare version of a Woody Allen film. Allen has written neurotics, but never so neurotic as here. He has written troubled women, but never the sociopathic lunatic that is Cristina Ricci’s brilliantly out-of-place Amanda. It’s an ambitious, critical reframing of pretty much every trope for which Allen is known and to such an extreme that the material seems intentionally sucked of oxygen. It is also often rather beautiful to look at it.

Melinda and Melinda (2004) boasted another wealth of talent– Rahda Mitchell (as Melinda), Chloe Sevigny, Chiwetel Ejiofor, Will Ferrell, Steve Carrell, Josh Brolin, Amanda Peet and Brooke Smith– and an interesting central idea, but it was, unfortunately, a dud.

Match Point (2005) was both a return to form and very much not. The film returned a sense of propulsive narrative momentum that seemed to have faded from Allen’s cinema, but it had some terrible elements: it’s premises and conclusions were the grimmest simplications of Dostoyevsky and Dreiser, and its central performances: Jonathan Rhys Meyers with a facial range akin to a Botox recipient, and Scarlett Johansson dealing with some schizophrenic writing, are some of the more off-putting to appear in an otherwise reasonably well-cast movie.

Scoop (2006) was maybe Allen’s most forgettable comedy.

Cassandra’s Dream (2007) was an actual tragedy, in the sense of existing in a morally and spiritually consequential flesh-and-blood world, and it explored a kind of rare, vulnerable masculinity rarely seen in movies, wonderfully captured in a writhing Colin Firth. It also had a pervading strangeness (the kind that would haunt the hermetic Allen’s every remaining film) in that it also seemed made by a Martian and peopled by them.

Vicki Cristina Barcelona (2008) also had a brisk narrative energy, but Allen, enchanted by Europe, still could not help but baste even Spain in New York neurosis. Penelope Cruz and Javier Bardem steal the screen from their American counterparts, but yet the American’s trivial issues are paramount. The film is also marred by a voiceover that is almost autistic.

Whatever Works (2009) took a screenplay Allen had written in the 1970s, for Zero Mostel, and gave it to a sensational cast led by Larry David. The film was mostly a joy, like a time-capsule, a paean to a dying form of film comedy. The film opens up like a flower when Patricia Clarkson enters. It keeps on blossoming from there and ends in the best version of Allen’s oft-repeated Auld Lang Syne News Years Eve finale.

You Will Meet a Tall Dark Stranger (2010) was a mess, Allen’s most forgettable drama.

The biggest popular success of Woody’s career, Midnight in Paris (2011) took the “nostalgic fantasist” tendencies of Allen to their ultimate, and often very funny, conclusion.

To Rome With Love (2012) blended some of the charms of Midnight in Paris with the ensemble ideas of You Will Meet a Tall Dark Stranger and the tourist wonderment of Vicky Cristina Barcelona into something that succeeded a bit more, just a bit more, than all of those films. The best section, starring Roberto Benigni, actually reframed the central conceit of Celebrity into a briskly funny and more effective version of that film.

Blue Jasmine (2013) had a completely different energy than Woody Allen fans had come to expect. Cate Blanchett was every bit as strong as to justify her many awards, and the picture itself, while not close to perfect, was very successful in its vicious deconstruction of the elite.

Magic in the Moonlight (2014) like Woody’s three prior pictures, looked wonderful. Too bad it was another dud, only slightly more memorable than Scoop because of its languorous, luminous images.

Irrational Man (2015) was too insane to call a dud, but it was nonetheless a terrible picture, almost compelling in its badness. It was also an example of the more bilious Woody, and it was hard not to read the film as a very (very) ugly commentary on the Allen/Farrow custody hearing.

Cafe Society (2016) was yet more overfamiliar tropes, now rendered as a period piece, set in 1930s Los Angeles, but not believably so even though quite pretty to look at. Allen’s cinema was beginning to fade.

Wonder Wheel (2017) was yet more of the same, but even worse.

A Rainy Day In New York (2018) was, surprisingly, kind of wonderful. There was not a bad performance in the many. Elle Fanning was, frankly, terrific. Cherry Jones delivers one of the finest monologues of both her and Allen’s career. The film was a rousing success.

And then Rifkin’s Festival (2020) was an embarrassment, Allen playing with themes much more finely done in Deconstructing Harry.

Coup De Chance (2022) was also an embarrassment, but in French, and boasted the worst and perhaps ugliest ending of Allen’s oeuvre, a sick irony in a career now stretching 50 feature films.

WORKS

The often bizarre, episodic Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex* *But Were Afraid to Ask (1972) is another broad comedy. Adapted from the 1970s “sex manual” by the psychiatrist David Reuben, it is broken into seven segments of differing length and quality. Like much early Allen, it has aged fairly well with the decades, indicative of an innate curiosity and clear comedic intelligence, but just don’t ask the Farrow supporting jihadists in the comment section. The first segment, featuring Allen as a court jester who uses an Aphrodisiac on the queen, is among the least funny. Along with later segments centered around cross-dressing and perversion, they’ve aged the least well, are the most imbued with Allen’s too-unsubtle Freudianism, and have the lesser jokes. The best segments take the biggest risks. A smirkingly disturbed segment wherein Gene Wilder falls desperately (and sexually) in love with Dolly the Armenian Sheep. Allen as an Italian newlywed escaped from a Fellini film, replete with shades and constant cigarette– and speaking Italian to boot– who learns his wife (Louise Lasser) can only get off when they have sex in public. A laboratory experiment gone awry that unleashes on the unsuspecting countryside a building-sized and threatening, lactating tit. A bit within the many command centers inside of the body of a man on a date– featuring Allen as a sperm– and Burt Reynolds as something like the Colonel of Ejaculation. It’s quick, cheap fun– very slight. (w: Woody Allen, c: David Walsh)

Sleeper (1973) revives a cryogenically frozen health food store owner from 1973 Greenwich Village in the year 2173, where the US has become a technofascist police state.

Love and Death (1975) is rather easily Allen’s best “early funny” picture. A revue of Russian literary conceits, Allen takes bigger risks all around and begins to explore tropes and themes that will figure throughout his body of work. Starring Woody himself as Boris, Diane Keaton as Sonja, James Tolkan perfectly cast as Napoleon, and a host of bit parts, the film is scene to scene, sequence to sequence, uniquely, rousingly funny. I won’t belabor the jokes, nor the plot. Keaton is a rather brilliant comedic actor and the chemistry that anticipates Annie Hall and Manhattan includes philosophical doublespeak further matured in both of those films. In the funniest example, they debate the meaning of life in the context of whether or not to assassinate Napoleon. This rolls into a sequence that rivals anything Allen did for physical comedy. (w: Woody Allen, c: Ghislain Cloquet)

The spirit of innovation enlivens Annie Hall (1977), an entirely different kind of film for Allen. From its opening moment there is a disarming honesty and vulnerability to the work so brazen that few filmmakers have ever dared try to copy it, and those who have tried succeeded only in pointing out their own artistic and/or comedic inadequacy. The marvel here is how Allen weaves character and material so tightly that they can’t be separated. The film is called Annie Hall— its own irony, because the film is Alvy Singer. It begins with a sardonic and wistful monologue by Allen as Alvy, where he establishes the first of two jokes that indicate that his participation in the film is more hesitant than we’re led to think, and that any one of us could be his stand in. His confident nonchalance in doing this served from the start to betray the artist: this is artifice, but audiences proved unable or unwilling to separate Allen himself from his own character. This is probably not unreasonable. Because Allen had the audacity to regard his own characteristics and preoccupations as of sufficient interest to carry a picture, he did little to mask it. But I think many who regard the film tend to miss a certain possibility manifested in the combination the jokes that begin and end the film: that this is Alvy’s story at all is merely a story-telling necessity. Allen is striving for something universal. The film traces Singer’s early life in Brooklyn and into his adulthood as a successful comic in Manhattan, through a couple of marriages, and finally to his brief but wistful relationship with the titular Annie Hall (Diane Keaton). This is only clear cumulatively, because it unfolds like a paper-fortune. Time folds back on itself several times, resonances echo throughout different sections of the film, and even the film’s own memory is questioned. One of Allen’s great gifts is that his films retroactively improve themselves as they move along. In his best work, the beginning of an Allen film is improved– retrospectively, in its very energy– by what emerges from it. An almost nausea-inducing jealousy has undoubtedly accompanied many an honest screenwriter’s assessment, as they reckon with how blithely effortless are Allen’s successes. He collapses the fourth wall and invites the audience directly into his story. He allows characters to collapse the internal logic of their own timelines, to talk with one another or comment on each other like time travelers. And characters reveal themselves in their full dimensions almost instantaneously. Perhaps there is a clue into Allen’s nonpareil skills as a dramatist in how deeply he understands idiosyncrasy, in others as much as himself. Keaton, in her first full revue of Annie, a charmingly erratic conversation following a tennis match, has quirks so embodied she practically leaps out of the frame. Allen, an admirer of Freud, would hardly consider an idiosyncrasy to be just that. Much of the brilliance of the writing is in how many ways he– his first career was as a groundbreaking stand-up comic– successfully threads “callbacks” into his material that serve as Freudian revelation and irony. The working title for the film, “Anhedonia,” is itself a psychological term indicating an inability to feel pleasure. Alvy’s living quandary is that he’s such a defensive creature, so overburdened by narcissism, that he simply cannot love anyone but fleetingly. To wither commitment (and its attendant pain) he sprays sardonic quips that deflect, insult, and diminish. They are like repellent from his mouth, even in the midst of scenes that would play better without them. One might say this is a weakness of the film, but the point is that the man can’t help himself. While this in theory sounds off-putting, it happens that they are also often extremely funny. He’s the butt of his own jokes. If you don’t laugh at them, there’s a quote by Yogi Berra that could be just as well be Alvy’s: “There are some people who, if they don’t already know, you can’t tell ‘em.” The unsentimental poignance of the film’s conclusion undermines all his quips, and the last absurd and brilliant joke is both the soul of humor and maybe finally not so very funny after all. (w: Woody Allen & Marshall Brickman, c: Gordon Willis)

The interiors of Interiors (1978) are static, obliquely shot, frigid prisons which are rendered with such stately meticulousness by cinematographer Gordon Willis that, in their implacable beauty, they momentarily lull one into forgetting that this is Allen’s first attempt at pure drama and that the film’s very existence is one of the greatest oddities of the American Cinema. Nothing could have prepared audiences or critics fresh off the inventive breeziness of Annie Hall for this bleakest of films. It revolves around a smothering, emotionally abusive matriarch, Eve, portrayed by Geraldine Page. The performance is a triumph, so discomfiting that listening to Eve’s listless and barely enunciated passive aggressions is enough curl your toes. When her husband, Arthur (E.G. Marshall), announces over a family dinner that he is leaving her, the respective age of his daughters to his left and right and his own geriatric demeanor attest to a man of almost inhuman patience. One of Allen’s gifts: this characterization is so quickly realized that it even survives the strange, affected rhetorical formality of the speech, and of nearly all the film’s dialogue. But that everyone in range of Eve can’t be any way other than strange and affected is perhaps much of the point. The film finally becomes about the sisters. Joey (Mary Beth Hurt) is infertile as an artist but quite fertile as a woman. She laments the aborted children as being the wrong kind of progeny. Meanwhile, her sister, Renata (Diane Keaton), is artistically fruitful but existentially burdened. A famous Allen quip: “I don’t want to achieve immortality in my work; I want to achieve it by not dying.” is an infinitely more succinct way of putting her plight. The plot as it progresses is punctuated by dramatic outbursts that are frightening in their suddenness. Eventually, Arthur remarries the “unsophisticated”, motherly Pearl (Maureen Stapleton) and the very modest reception culminates in the film’s strongest moment. The performances are all good: Sam Waterston and Richard Jordan as the sisters’ husbands, Krystn Griffith as the third sister, Flyn. There are gentle, languid walks on the Long Island beach that Willis captures in smooth telephoto tracking shots that do ring of Bergman. Allen way overburdens the point (and probably credulity) by having Jordan’s forcibly narcistic alcoholic Frederick devolve into a psychopathic rapist. This, before the films wrenching finale, which, while telegraphed, is leavened by a searing monologue from Hurt, renders the film finally too dismal, which critics seized on and audiences despised. More bitter perhaps than even Fassbinder’s bitter tears. (w: Woody Allen, c: Gordon Willis)

Allen leavens his next film. Both bitterness and whimsy imbue Manhattan (1979), a magnificently directed comedy about how the heart beguiles fundamentally lonely, cerebral (and selfish) people. Here the perfectionist austerity of Interiors is transformed by Gordon Willis into pictorial grandeur and museum-piece silhouettes of such consistent compositional and luminous beauty that his photography will survive on certain shortlists perhaps for centuries. If those lists stall out due to a bygone art, and pitchfork wielding court-of-public-opinion jihadists don’t succeed in burning the negative (something Allen already tried to do), the lensman’s permanent placement may win him the kind of immortality Allen least prefers. This beauty is in the service of romanticism, but for the city itself. As Isaac Davis, Allen dictates from his character’s novel over the film’s rousing opening montage: “He loved New York. He idolized it all out of proportion.” This is over Gershwin’s Rhapsody in Blue, and it soars. But Isaac loves New York for his own cocoon. Within it is available all kinds of novelties: culture, music, food, art, literature, architecture– but also social arrangements that allow him company with cultural elites, all while decrying them, and the permissive, faux-enlightened-class promiscuity that has him torn between a 17-year-old (Mariel Hemingway) and the mistress (Diane Keaton) of his closest friend (Michael Murphy). Shot almost entirely in extended dialogues, there isn’t a single moment in the film that doesn’t involve talk. These winding dialogues are acted by a cast so in tune with the material, and so supportive of each other beat to beat, that a then 17-year old Mariel Hemingway managed to woo the Academy. Much of the intelligence in the dialogue involves how insecurity compromises true intelligence. There is no better tell-tale of the hack than to spit on universally acknowledged masterworks, which is one of the revealing tendencies of its many blathering fools, including Diane Keaton’s Mary. There’s also an innate immaturity in those that isolate and sanctify only their own views. The fact that Isaac’s ex-wife has the audacity to intrude upon his own perception of the past is very telling. His concern is that the ugliness of their divorce will be “all out in the open”. It’s magnificently written. Allen also delivers the most naturally embodied performance of his career. And I mean that to cut both ways. That Hemingway’s Tracy emerges as the least impetuous, most adult character on screen is, of course, much of the point of the film. Allen’s reputation in the public is (at its kindest) as a neurotic, but it’s his blitheness that invigorates his admirers and galls his detractors. He gives himself more rope– just enough, in fact. For all his kvetching about his existential unluck, the temporal luck of his certain professional gifts– how they accorded with his place and time– afforded him the only kind of life that could inform a film of this arrangement. Call its sensibilities European– whatever, Allen’s completely self-assured mélange of high-brow and low-brow with analysand pontification, literary pretension, French permissiveness, and Swedish pessimism came about probably because he was first very rich and famous. The film’s configurations are so hermetic, they essentially entrap the film’s themes. These people are not worried about maintaining a career insomuch as further maximizing one, and since they are unsure of most everything beyond self-absorption, they have time to complicate each other’s lives. That nothing beyond petty complication seems to happen in Manhattan is part of its alchemy– both part of its appeal in its time and to the puzzlement of later generations. Finally though, while Allen makes clear in his material that he is aware of this, he does ask us to feel more, to empathize further. “Have a little faith in people,” Tracy recommends. Was life in New York once actually like this? Well, yes and no. The truths the film captures so poignantly of course were lived everywhere, and still are (though increasingly less with the involvement of minors)1 which is why it was so warmly received. But the picture makes it very hard to imagine Travis Bickle driving down the road. Maybe, thanks to Bickle’s strenuous efforts, Tracy could become tutor to Iris Steensma. (w: Woody Allen & Marshall Brickman, c: Gordon Willis)

Stardust Memories (1981) weaves ideas from Fellini and Bergman into a threadbare meta-film tapestry. Allen stars as Sandy Bates, a filmmaker with a resume comparable to his own, who’s been invited to a retrospective of his life’s work at a Jersey Shore hotel called “The Stardust”. The movie opens with what is effectively the ending of Bates’ newest film, where he “borrows” the opening of Fellini’s 8 1⁄2 and relocates it to a train. The one Sandy is riding on is stultifying, and seems passengered by semi-deformed misfits. But there’s another train over there on those other tracks and they’re having a big party, a gay old time. Sandy wants off, but there is no exit. As he and his wretched bunch pull out of the station, a young Sharon Stone blows him a kiss from the other train. You can read some macabre resonances from history into the scene. It’s somewhat Bergmanesque in the way that it states its ideas and then does not leave. It doesn’t appear that Bates has much of a future in drama. That, in fact, is part of the dramatic thrust of Stardust Memories. It turns out the passengers on both trains were on their way to the garbage dump. When they get there, they walk about aimlessly, most of them nonplussed. The cheap metaphor is probably meant to be cheap, and frames ideas within the film that are central to much of Allen’s work: Of what worth is art in the face of the fact of death? How should a life be spent in the face of the fact of death? To what degree should we sacrifice our time and energy for love and art in the face of the fact of death? You can spot the preoccupation. It is a worthwhile one, but Stardust Memories chases these ideas around and never really meaningfully takes hold of any of them. The film is more a series of impressions and personalities and stylistic devices, a few of which work, because Allen can be very funny and because Gordon Willis (working in Black & White again here) is often inspired. Another forceful presence– presence more than personality– in the film is a gaunt, delicately beautiful Charlotte Rampling. But the film is callous with her, as it is with Sandy’s many fans, who he seems to regard as only so many leeches. Her arc eventuates in a montage of strong effect, where Rampling exhibits a complete mental collapse. The film doubles-back to relish her beauty, but just her beauty. The camera hangs on her for a full minute and seems to point out only that we learned nothing more than that she was troubled. Elsewhere, at a gathering at his sisters, after Sandy spots a bruise on her face, a guest tries to relay to him her experience of being gang raped. He shrugs her off. These items and many more point to an ugliness or disregard just under the surface of the film that has a hostile bitterness to it, that, even though is manifested in the film literally in the form of shapeless beast, lingers in the mouth after it ends. (w: Woody Allen, c: Gordon Willis)

Woody less ambitiously channels Shakespeare via a Bergman masterpiece, Smiles of a Summer Night, with A Midsummer Night’s Sex Comedy (1982). The cast is great, the photography is stunning, there are several laughs, but the whole thing comes together to a charming shrug. Mia Farrow, Jose Ferrer, Tony Roberts, Julie Hagerty, Marie Steenburgen and Allen gather in the New York countryside for a wedding, whereupon relationships devolve into sexual duplicity and poignant ruminations on lost love. Everyone tries to, or does, screw everyone. That’s all off camera, of course. Even though he never shuts up about it, Allen would never dare film sex. He and Gordon Willis do manage to make the landscape– the ponds and lakes and trees and fauna– sumptuously ethereal. This is like a visual evocation of the thrust of the film, which is about the fleeting nature of love, and the recurrent nature of lust. “Sex alleviates tension and love causes it,” Allen’s Andrew says at one point. There are at least a couple of montages of breathtaking textural beauty almost unfit for the casual silliness of the film. The film is so tidy and clean that it’s facile prop gags and physical comedy is boring. Even the scenarios of sexual sneaking are droll. As ever, if there is comedy, it is in Allen’s sharp quips. He never even bothers to disguise that he is a 1980s New Yorker in this 1906 “period piece”. So often, when Allen strives for Bergman, a vast crevasse between the artists comes into view which, in this case, is massive. (w: Woody Allen, c: Gordon Willis)

Broadway Danny Rose (1984) has some of Woody Allen’s most effervescently delightful writing. If one were to attempt a taxonomy of Allen’s films, this would be a particular species. Call it the “nostalgic fantasist comedy”. Danny Rose’s story is told in flashback, relayed from a Carnegie Deli table by a group of old Broadway comics (Sandy Baron, Corbett Monica, Jackie Gayle, Morty Gunty, Will Jordan, and Howard Storm, all playing themselves). This structure creates myth. And Gordon Willis shoots it in the same gorgeous black and white palette he used for Manhattan. Allen writes the comics like he’s been at that table too. He almost certainly has. The film seems to long for the Broadway good ol’ days– a pre-corporatized Broadway– and the charm of Danny Rose is that he is the last man holding the flame. Because of this the film plays like a form of historical longing. Allen stars as the titular, a one-man talent agency for talented misfits and down-and-out lounge acts: one-armed jugglers, piano-playing birds and a has-been Italian lounge lizard with a drinking problem. He’s the kind of guy who will meet someone of modest talent and promise them fame and riches, not because he’s a swindler, but because he loves the hustle and the people. Allen is wonderful as Rose. The character seems to triangulate his talents perfectly and he doesn’t come off as merely trying to play himself. He also has a heart. The film is warm, relaxed and funny. Rose is tasked to convince his client’s angry girlfriend to attend his big show at the Waldorf. Milton Berle will be in attendance. His name is Lou Canova, and he’s a slovenly, alcoholic embarrassment played nicely by Nick Apollo Forte. His girlfriend, Tina, has Mia Farrow stretching herself a bit beyond her typical tenuous mutterings and looking like what might best be described as Italian Gangster Girlfriend Barbie. Much of the comedy is simply funny on its own terms– the quips are wonderful, and there’s even a slapstick bit involving nitrous oxide. But the heart of the film comes through in Rose’s unspoken, utterly assumed kindnesses. When Tina finally realizes what kind of man he is and comes back to apologize for her dishonesties, he’s hosting thanksgiving for his misfits. He seems to take it for granted that he should feel lonely, so long as they do not. This is a lovely movie. (w: Woody Allen, c: Gordon Willis)

The Purple Rose of Cairo (1985) is whimsical, saddened, and, though slight, culminates in an emotionally truthful stab. It stars Mia Farrow as Cecilia, a day-dreamer whose obsession with the movie house seeps into her every waking hour. When we meet her, she is standing in front of the “Jewel” movie house, admiring a poster for “Top Hat” with Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers. Irving Berlin’s “Cheek to Cheek” plays on the soundtrack and Gordon Willis’ image pops with grains and hairs. Then a hunk of metal from the marquee nearly falls on her head. Cecelia has a tough life. Her husband, Monk, is a brute who is played in that classic Danny Aiello way of both imploring charm and hand-wringing rage, often within moments of each other. He takes as much of her money as he can in order to shoot craps with the boys, a bunch of laid-off factory workers. That is, until her dreamy infatuation with the movies gets her fired from her waitressing job. At the “Jewel”, “The Purple Rose of Cairo” has begun a one-week stint, and Cecelia goes and is charmed by the tale of Tom Baxter (Jeff Daniels), an archaeologist and treasure hunter (think Indiana Jones with a modest brain injury) being introduced to Manhattan high society. Allen recreates the film within a film with great and vivid attention to detail. It really is almost convincing as a particularly lousy picture of the 30s. The implication, naturally, is that the theater is Cecilia’s escape from the perils of her life in this depressed, survivalist New Jersey hellscape. She goes to the movie for seemingly every showing, until Tom Baxter, in a scene we’ve watched now a half-dozen times, does something strange: He stutters his lines, gets distracted, and then turns to her, “My God, you must really love this picture.” And then he walks out of the screen and into her life. Allen can be terrific with these fantastical ideas. He is a smart enough dramatist to seemingly always take the tougher, more rewarding road. So this is not Cecilia’s fantasy, but a local scandal witnessed by every theater goer, the reality of which eventually lands directly on the studio’s nonplussed lap. Cecelia and Tom fall some way in love, but he’s a challenge: he only knows what’s been written into his character, and his propensity to hand out movie money has him engaged in criminality and lunacy in equal measure. When Monk learns of the affair, they fight– and the brute wins because Tom would never fight dirty. Naturally, the studio brings in the actor who played Tom, one Gil Shepherd. When he arrives on scene, Cecelia introduces him to his de-celluloided double and they argue with one another in a slick, invisible split screen. The effects are impressively seamless for Allen and Daniels is wonderful on both ends, particularly in how he’s wooed by Ceclia’s sincere compliments. The woman would make a good critic. Allen has great fun at modulating Gil’s talent and ego. There’s an utterly charming scene where Cecilia strums the ukulele to piano accompaniment as Gil croons along. In the scene, Farrow legitimately looks like she’s having the time of her life. I won’t reveal the ending but to say that much of the film’s searing poignance comes from it. It works so well it continues to this day to piss people off. There’s a sting to it and it serves as a better profession of love for the movies than any happy ending possibly could. (w: Woody Allen, c: Gordon Willis)

The ensemble comedy Hannah and Her Sisters (1986) borrows its structure from Bergman’s Fanny and Alexander, framing three sisterly microdramas around three successive Thanksgiving holidays. They are announced by clever title cards that serve as descriptive punctuation, such as: “God, she’s beautiful…” and “The hypochondriac,” which were themselves satirized around the film’s opening by Jean Luc Godard in a small interview film entitled Meetin’ WA that was either just idiotic, or cruel and idiotic and infantile all at once, depending, I suppose, on one’s view.2 Allen’s writing, even when his characters’ arcs stretch as little as twenty minutes of run time, affords such clarity for his cast that they are all uniformly marvelous. But the film is also rather thin in its runtime, the stories too truncated. Mia Farrow stars as the titular Hannah. She’s an unusual heroine: enabling but kind to her sisters, loving of her troubled parents, supportive to a fault. Allen is wonderfully observant and the very structure of Hannah’s family is itself familiar and lifelike. The sisters are Diane Wiest as Holly– one of Allen’s classic neurotics who jump from one aspiration to the next– and the beautiful Lee, played by Barbara Hershey. Lee, it so happens, is the object of the infatuation of Hannah’s husband, Elliot (Michael Caine). She is mired in a failing relationship with Frederick, a pretentious painter played by Bergman staple Max Von Sydow. Every character on screen, with the exception of Hannah, seems hardly able to sit still and think. They are clear as characters because their neuroses absolutely govern them and they flit from one indulgence to the next. As dramatic constructions, there isn’t much to them beyond impulsiveness. I think this is part of the universal appeal of the film: it’s very, very simple. I also think it’s the primary fault of the film. So Lee and Elliot begin an affair and it turns out– no surprise– to be something neither of them actually needed. It’s rather brazen how cerebral (read: how close to sociopathic) they are in justifying their behavior, given the betrayal involved. Does this accord with Allen’s personal values? Well, yes, it probably does. Meanwhile, Holly skips from one calling– and subsequent disappointment– to the next. At one point, Hannah tries to set her up with her ex, Mickey (Allen). She’s so addled with drugs when they go out that it ends in disaster, but does afford the hilarity of witnessing Allen’s perception of a post-punk concert. He begs her to leave and they go to a piano bar. “I was so bored!,” she yells, as they part. “Yeah, that’s tough,” he replies, “You don’t deserve Cole Porter. You should stay with groups that look like they’re gonna stab their mothers.” Mickey, a hopeless hypochondriac, is the film’s most vivacious character. His arc has him descend into an existential crisis. He is– at least as he perceives things– nearly diagnosed with cancer. But after he finds out he’s perfectly healthy, only then does it dawn on him that the day will come when the news is not so good. “You’re just realizing this now?,” his producing partner Gail (the always charming Julie Kavner) asks him. “Listen kid,” she admonishes him, “I think you snapped your cap.” His voice-over ruminations and sardonic endeavors in embracing world religions are so funny Allen nearly smothers his own point. They also have a new cinematic energy, a more workmanlike manner (yet, oddly, no less ornate– or stuffy?– than Gordon Willis’ formalism) by Carlo Di Palma. Mickey’s tale is a very typical Allen trope, essentially an elongated, dramatized version of Isaac’s monologue toward the end of Manhattan. It’s hard to imagine the film without his story line, and, when imagining it removed, the picture comes to reveal itself (perhaps, because there are small charms everywhere) as basically a couple of bland stories framing an excellent short comedy. Because of the pleasant conclusion to it all– an anti-Purple Rose ending so pleasant in fact, it’s hard to believe Allen himself believes it– the film emerged as one of his biggest successes to date. (w: Woody Allen, c: Carlo Di Palma).

Woody follows up his over-acclaimed Hannah and Her Sisters with Radio Days (1987), a masterpiece of comedic writing and nostalgic remembrance. Allen, even to this point, has contributed massively to the American Cinema. His greatest contribution to American culture, however, both predated his films and then later imbued them with a characteristic brilliance that was his auteur stamp: his genius for cerebral comedy. Radio Days is the greatest exhibition of that Allen comic sensibility that hews to the universal and away from the intimately ugly, most resonant of the brilliant prose writing that was a seemingly effortless extension of his stand-up work. As I just wrote, Allen’s films can be ugly in an intimate way. Most of his films to this point have been– putting it kindly– from a man with the peculiar mores and concerns of someone who regards themselves and their pre-occupations on another strata of being. They argue a value system that doesn’t always accord with, say, mere day-to-day, working humans, which is precisely what he writes about here. Ironic that implicit in much of Allen’s work is this sense that he forgets the realities of where he came from. The film manages to play as a series of episodic sketches that accumulate, like pieces of a puzzle, or like a kaleidoscope, into a moving portrait of a New York family from the late 30s into the war years. This world he renders with the most loving regard, because it was his: this family lives in Rockaway Beach, about three miles as the crow flies from Allen’s own Midwood, Brooklyn. Everything, from the extraordinary art direction and set design of Santo Loqausto, Carol Joffe, Leslie Bloom, and George DeTitta Jr., to the period music and costume, to Carlo Di Palma’s vibrant frames, to the perfectly pitched performances of the voluminous cast, is historical filmmaking of the highest order. It is hard not to be fulsome. It is also hard to be thorough, as this is by far Allen’s most ambitious film. When considering Allen’s potential influences, one naturally looks first to Bergman and Fellini. The best comparison here is Fellini’s Amarcord, a title that was a play on the pronunciation of “a m’arcôrd,” or “I remember” in the Romagnol language. Radio Days is a remembrance of an era when a different medium than television interjected into the homes and lives of Americans and, in its way, created new atmospheres. These were musical, topical, diversional, corporate, sometimes seemingly existential interjections. Allen recreates it– its camp, caprices, charm, criminality and all. Allen himself narrates as “Joe”, and a central character is the young Joe, a boy played by Seth Green, representing something like a young Allen. His parents, Julie Kavner and Michael Tucker are listed in the credits as merely “Mother” and “Father”. His mother keeps the house. His father drives a cab, something we find out later in the film in a poignant moment. He’s a young Jewish kid in a time where Queens and its beaches are his playground. He loves– they all love– the radio: “The Masked Avenger”, “Guess that Tune”, the patriotic hero “Biff Baxter”, the stuffy Manhattanite musings of “Breakfast with Irene and Roger.” His Aunt Bea (Diane Wiest) loves the music, delights in dancing around the living room. She’s looking for a husband, but when she gets close to making-it in the car with her date, something like Orson Welles’ broadcast of War of the Worlds cuts in to warn of invading Martians and he runs from the vehicle in abject terror. She ends up walking the six miles home. Mia Farrow elsewhere stars as a cigarette girl at a ritzy club who, after taking diction lessons, transforms her grating New Yawk squeak into a rounded and lavish radio voice, something to hilariously obscure the fact that she is as dumb as a tree stump (“who’s Pearl Harbor?” she asks after the “Day of Infamy” broadcast). Anecdotes like this make up the small, puzzle-like pieces of the film and the time. They are, each and every one, delightful and funny, sometimes uproariously so. Okay, so comedy is somewhat de gustibus, but in its final act the film transforms into something more. There is, particularly in one movement, the sense of something lost– something communal and humane. The bit involves that classic national cliffhanger: a young girl falls down a well and emergency workers try to rescue her. When the broadcast starts Joe’s father is smacking him senseless, and as it develops he stops slapping and rests his hand on the boy’s head, and then as it reveals what awfulness is at stake he embraces the child. The family and the nation wait in rapture, hanging on the newscaster’s every word. It becomes easy to laugh at what one might expect to be a satire of our collective gullibility, and how the media has come to play to our needs and expectations as though it were our tuning fork. What fools we were, even then. Except the girl doesn’t live. They pull out a dead body. Allen doesn’t show this of course, but his broadcaster is all the more poignant for simply describing it as a horrible tragedy, and ending his report on a note of sadness. And so, all over the country– and in Joe’s kitchen in particular– families embrace one another in stunned silence for comfort. And then one tumultuous year turns to the tumultuous next: 1944. (w: Woody Allen, c: Carlo Di Palma)

Allen shot September (1987) twice, the first time with an entirely different cast, including Sam Shepherd, Maureen O’Sullivan, and Charles Durning. The cast we get to see features Elaine Strich, who plays the narcissistic sociopath Diane, modeled perhaps on Lana Turner. Her Daughter, Lane, played by Mia Farrow, a woman recuperating from a suicide attempt. She is a tortured mouse of a woman, never recovered from a family tragedy, where at 14 she presumably shot and killed her mother’s abusive lover. This is all loosely inspired by the Turner/Stompanato scandal of 1958. Allen drops it into a slight mold modeled after “Uncle Vanya,” by Checkhov and limits the drama to a single Vermont home. Diane is essentially Eve from Interiors, but with a different more extroverted life-force. Her remonstrances and pronouncements are every bit as toe curling, and perhaps more sociopathic. Her refrain is essentially to blithely disregard her brutal past and is blind to the fact that she is the sole beneficiary of such madness. What is revealed of this is sharp and probably truthful, but Allen blunts its impact by needlessly entangling his other characters in mores and pursuits he’s done better elsewhere. Diane Wiest, as Lane’s conflicted friend, Stephanie, is the object of the overweening affection of Peter (Sam Waterston). If this also seems familiar, it should. Though they are not sisters, Lane and Stephanie suffer through the same dynamic of betrayal forced by those lust-intoxicated men in Interiors and Hannah and Her Sisters. So this is a retread in a few dimensions, none of them an advancement. Even Carlo Di Palma’s claustrophobic interiors make the film feel small. There’s an apt visual metaphor in the form of a game of pool. Denholm Elliot and Jack Warden fill out the rest of a cast of misplaced amour, in each instance love and infatuation striking people with a kind of deafness and blindness that has them ricocheting off of one another hopelessly. (w: Woody Allen, c: Carlo Di Palma)

Another Woman (1988) is perhaps Woody Allen’s most successful drama and his best appropriation of Bergman– a take on Wild Strawberries frank psychological undressing and Persona’s mutualist dualities, that, because it’s less leaden than Bergman’s work, has more raw emotional impact. The film is an interior study of Marion Post (Gena Rowlands), a philosophy professor working on a new treatise while at an emotional crossroads in her life at large. The control with which she so studiously contoured her romantic, professional and social life has come finally to reveal its inherent emptiness. She is in a loveless marriage, essentially friendless, without visibly rewarding professional accomplishments, torturing herself with remembrances of lost opportunity, particularly as regards Larry (Gene Hackman) who, though she spurned, was perhaps her final opportunity for true passion. She also bolsters her sense of self by mentoring her husband’s daughter (Martha Plimpton), a kind of proxy motherhood. Not that a lack of children is a character flaw– only that she approaches motherhood in this relationship theoretically, as she approaches everything. She’s stone cold. One would liken her to Isaak Berg’s own self-described “pedant,” and she regards herself in monologue in the same measured, scientific tone. Because nearly all of Allen’s 1980s films feature upper-middle class intellectuals, he has been accused of considering himself one of them, or of being one of them. I think this is false, practically impossible given his near obsessive compulsion for constant work. If he doesn’t resent them, he at least has profound sympathy for many of them. He regards them, I think, as the writer Nassim Nicholas Taleb has referred to them: as IYIs, intellectual-yet-idiot. There is, on the surface veneer of Marion, a rank snobbery and a ghastly stench of self-seriousness that renders her, finally, stupid. As Marion settles into her downtown sublet, in order to work, the self-recriminating voice of Mia Farrow’s “Hope”– an on-the-nose name if there ever was one– is the only gateway to honesty possible for someone who has armored herself with Marion’s degree of haughtiness: the voice must cut through from the outside. Roger Ebert makes a lovely observation that Allen allows Marion to smother out the intrusive voices using a couple of mere pillows pressed against a grate. The easy muting of such clear audibility is totally phony, unless you consider that perhaps what Hope is saying is not, in fact, what she’s saying– but perhaps what Marion is saying to herself– the nightmare alternate reality that she needs to hear to save her own life. This “othering” of one’s own subconscious is a very elegant transmutation of the Freudian conceits that Allen holds so dear. It also happens to be a rather more beautiful submission for the capabilities of the unconscious than Allen typically admits. It’s quite humane and a certain gentleness slowly emerges from what seems like an otherwise cold film. The cinematographer Sven Nykvist helps with that sense of coldness, brought on to lend a sedate stillness to these scenes. Their evocation of the manifold possibilities of voyeurism in urbanity feels true. Marion even manufactures a meeting with Hope, but– also truthful– she uses the time to talk only about herself. Again, something else cuts through her own armor in this very scene, that we see only later, and that is the impetus for her to finally make the first major change she needs. (w: Woody Allen, c: Sven Nykvist)

With Alice (1990) Allen tries something interesting: he couples Carlo Di Palma’s gloomy, sedate, stuffy Central Park-streets aesthetic with comic, magical realist conceits, even going so far as to shoot visual gags like they were pure drama. A dash of the “herbs” of “Dr. Yang” (Keye Luke, in his final film) and Alice (Mia Farrow) can go invisible, reanimate deceased lovers (Alec Baldwin), even fly over the city as if in a dream. But it still looks like an art film, with resplendent set design and memorable costume touches (Alice’s red hat is strangely iconic given how little the film is remembered) by Santo Loquasto and Jeffery Kurland. This is a film that, like Another Woman, sneaks up on you and is infinitely better than its modesty suggest. The central idea is that its titular wealthy Manhattan housewife has repressed her own desires so deeply that she has consigned herself to an upper class prison, frittering away her days swiping the Amex card and carting her child around. She’s understandably (her marriage is clearly empty) enticed by the gently charismatic Joe (Joe Mantegna), the father of her son’s classmate. She tries and recedes, tries and recedes to consummate the affair, all while Dr. Yang decompresses her Freudian soul. The whole thing is lovely and light and funny in a way that makes you smile. And it has one of Allen’s more beautiful, humane endings. (w: Woody Allen, c: Carlo Di Palma)